Is the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston a Member of Roam

| |

Museum of Fine Arts primary entrance with the Appeal to the Neat Spirit statue | |

| Location within Boston Show map of Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Massachusetts) Show map of Massachusetts Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (the United States) Show map of the U.s. | |

| Established | 1870 (1870) |

|---|---|

| Location | 465 Huntington Avenue Boston, MA 02115 |

| Coordinates | 42°20′21″N 71°05′39″W / 42.339167°N 71.094167°Due west / 42.339167; -71.094167 Coordinates: 42°20′21″N 71°05′39″W / 42.339167°N 71.094167°W / 42.339167; -71.094167 |

| Blazon | Fine art museum |

| Accreditation | AAM NARM |

| Visitors | 1,249,080 (2019)[ane] |

| Director | Matthew Teitelbaum |

| Architect | Guy Lowell |

| Public transit access | Green Line (E branch) Orange Line Franklin Line Providence/Stoughton Line |

| Website | mfa.org |

The Museum of Fine Arts (oftentimes abbreviated as MFA Boston or MFA) is an art museum in Boston, Massachusetts. Information technology is the 20th-largest art museum in the world, measured by public gallery expanse. It contains 8,161 paintings and more than 450,000 works of art, making it one of the almost comprehensive collections in the Americas. With more than i.two meg visitors a year,[2] it is the 52nd–nearly visited art museum in the world as of 2019[update].

Founded in 1870 in Copley Square, the museum moved to its current Fenway location in 1909. It is affiliated with the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts.

History [edit]

1870–1907 [edit]

The original Museum of Fine Arts building in Copley Square

The Museum of Fine Arts was founded in 1870 and was initially located on the top flooring of the Boston Athenaeum. Most of its initial collection came from the Athenæum's Art Gallery.[3] Francis Davis Millet, a local artist, was instrumental in starting the art school affiliated with the museum, and in appointing Emil Otto Grundmann as its first director.[iv] In 1876, the museum moved to a highly ornamented brick Gothic Revival building designed past John Hubbard Sturgis and Charles Brigham, noted for its massed architectural terracotta. It was located in Copley Square at Dartmouth and St. James Streets.[3] Information technology was congenital almost entirely of brick and terracotta, which was imported from England, with some stone about its base.[five] After the MFA moved out in 1907, this original edifice was demolished, and the Copley Plaza Hotel (now the Fairmont Copley Plaza) replaced it in 1912.[6]

1907–2008 [edit]

In 1907, plans were laid to build a new home for the museum on Huntington Avenue in Boston'south Fenway–Kenmore neighborhood, near the recently opened Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Museum trustees hired builder Guy Lowell to create a blueprint for a museum that could exist built in stages, as funding was obtained for each phase. Two years later, the first section of Lowell'due south neoclassical design was completed. Information technology featured a 500-foot (150 grand) façade of granite and a yard rotunda. The museum moved to its new location later in 1909.

The 2d phase of structure built a wing along The Fens to business firm paintings galleries. Information technology was funded entirely by Maria Antoinette Evans Hunt, the wife of wealthy business organisation magnate Robert Dawson Evans, and opened in 1915. From 1916 through 1925, the noted artist John Vocalizer Sargent painted the frescoes that beautify the rotunda and the associated colonnades.

The Decorative Arts Wing was built in 1928, and expanded in 1968. An addition designed past Hugh Stubbins and Associates was built in 1966–1970, and another expansion past The Architects Collaborative opened in 1976. The West Wing, at present the Linde Family Wing for Gimmicky Fine art, was designed by I. M. Pei and opened in 1981. This wing now houses the museum's buffet, restaurant, meeting rooms, classrooms, and a giftshop/bookstore, as well as big exhibition spaces.

The Tenshin-En Japanese Garden designed past Kinsaku Nakane opened in 1988, and the Norma Jean Calderwood Garden Court and Terrace opened in 1997.[7] [3]

2008–nowadays [edit]

In the mid-2000s, the museum launched a major try to renovate and expand its facilities. In a 7-yr fundraising campaign between 2001 and 2008 for a new wing, the endowment, and operating expenses, the museum managed to receive over $500 meg, in addition to acquiring over $160 million worth of fine art.[8]

During the global financial crisis between 2007 and 2012, the museum's annual upkeep was trimmed by $1.5 1000000. The museum increased revenues by organizing traveling exhibitions, which included a loan exhibition sent to the for-profit Bellagio in Las Vegas in substitution for $1 million. In 2011, Moody's Investors Service calculated that the museum had over $180 million in outstanding debt. However, the agency cited growing attendance, a large endowment, and positive cash flow every bit reasons to believe that the museum'due south finances would become stable in the about future.

In 2011, the museum put eight paintings by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Gauguin, and others on auction at Sotheby'due south, bringing in a total of $21.6 million, to pay for Homo at His Bath by Gustave Caillebotte at a cost reported to exist more than $15 million.[ix]

On March 12, 2020, the museum announced that it would close indefinitely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All public events and programs were canceled until August 31, 2020. The museum reopened on September 26, 2020.[x]

Art of the Americas Wing [edit]

The renovation included a new Art of the Americas Wing to feature artwork from North, South, and Central America. In 2006, the groundbreaking ceremonies took place. The new fly and bordering Ruth and Carl J. Shapiro Family Courtyard (a bright, cavernous interior infinite) were designed in a restrained, contemporary style by the London-based architectural business firm Foster and Partners, under the directorship of Thomas T. Difraia and CBT/Childs Bertman Tseckares Architects. The mural architecture firm Gustafson Guthrie Nichol redesigned the Huntington Artery and Fenway entrances, gardens, admission roads, and interior courtyards.

The wing opened on November 20, 2010, with costless admission to the public. Mayor Thomas Menino declared it "Museum of Fine Arts Day", and more than than 13,500 visitors attended the opening. The 12,000-foursquare-foot (1,100 m2) glass-enclosed courtyard at present features a 42.5-human foot (13.0 m) high glass sculpture, titled the Lime Green Icicle Belfry, by Dale Chihuly.[11] In 2014, the Art of the Americas Wing was recognized for its high architectural achievement by the award of the Harleston Parker Medal, by the Boston Order of Architects.

In 2015, the museum renovated its outdoors Japanese garden, Tenshin-en. The garden, which originally opened in 1988, had been designed by Japanese professor Kinsaku Nakane. The garden's kabukimon-mode entrance gate was built by Chris Hall of Massachusetts, using traditional Japanese carpentry techniques.[12] [thirteen]

Collection [edit]

The Museum of Fine Arts possesses materials from a wide variety of art movements and cultures. The museum likewise maintains a large online database with information on over 346,000 items from its collection, accompanied with digitized images. Online search is freely bachelor through the Internet.[14]

Some highlights of the drove include:

- Ancient Egyptian artifacts including sculptures, sarcophagi, and jewelry

- Dutch Gold Age painting, including 113 works given in 2017 by collectors Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo and Susan and Matthew Weatherbie.[15] The souvenir includes works from 76 artists, as well as the Haverkamp-Begemann Library, a collection of more 20,000 books, donated past the van Otterloos. The donors are also establishing a dedicated Netherlandish fine art center and scholarly found at the museum.[16]

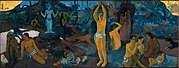

- French impressionist and post-impressionist works past artists such as Paul Gauguin, Édouard Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne

- 18th- and 19th-century American art, including many works by John Singleton Copley, Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, and Gilbert Stuart

- Chinese painting, calligraphy and imperial Chinese art

- The largest drove of Japanese artworks nether one roof in the world outside Japan

- The Hartley Drove of almost ten,000 British illustrated books, prints and drawings from the late 19th century

- The Rothschild Collection, including over 130 objects from the Austrian co-operative of the Rothschild family. Donated by Bettina Burr and other heirs[17]

- The Rockefeller collection of Native American piece of work[eighteen]

- The Linde Family unit Wing for Gimmicky Fine art includes works by Kathy Butterly, Mona Hatoum, Jenny Holzer, Karen LaMonte, Ken Price, Martin Puryear, Doris Salcedo, and Andy Warhol.[19]

Japanese fine art [edit]

The collection of Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts is the largest in the world outside of Japan. Anne Nishimura Morse, the William and Helen Pounds Senior Curator of Japanese Art, oversees 100,000 full items[20] that include 4,000 Japanese paintings, 5,000 ceramic pieces, and over xxx,000 ukiyo-e prints.[21] [22]

The base of this collection was assembled in the tardily 19th century through the efforts of four men, Ernest Fenollosa, Kakuzo Okakura, William Sturgis Bigelow, and Edward Sylvester Morse, each of whom had spent fourth dimension in Japan and admired Japanese art.[20] [23] Their combined donations account for up to 75 percent of the current collection.[20] In 1890, the Museum of Fine Arts became the first museum in the United States to establish a drove and appoint a curator specifically for Japanese art.[21] [24]

Another notable role of this collection is a number of Buddhist statues. In the later Meiji era of Japan, around the turn of the 20th century, government policy deemphasizing Buddhism in favor of Shintoism and financial pressures on temples resulted in a number of Buddhist statues being sold to private collectors. Some of these statutes came into the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts.[25] [26] Today, these statues are the subject field of preservation and restoration efforts, which have been at times viewable past the public in special exhibits.[26] [27]

Too important for this collection is the exhibition of its items in Japan. From 1999 to 2018, regular exchange of items was conducted between the Museum of Fine Arts and its sister museum, the now-airtight Nagoya/Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[21] [28] In 2012, the traveling exhibition Japanese Masterpieces from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston visited the Japanese cities of Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka and Fukuoka, and was well received.[xx] [21] [29]

Libraries [edit]

The libraries at the Museum of Fine Arts collectively firm 320,000 items.[30] The main branch, the William Morris Hunt Memorial Library, is named after the noted American artist. Information technology is located off-site in Horticultural Hall, ii stops away on the MBTA Green Line. The master library is open up to the public, and the itemize can exist searched online.[30]

Exhibitions organized by the library staff in coordination with the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts are opened two to iii times per yr.[31]

CAMEO [edit]

The Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online, (CAMEO) is a database that "compiles, defines, and disseminates technical information on the distinct collection of terms, materials, and techniques used in the fields of art conservation and celebrated preservation".[32] CAMEO uses MediaWiki.[33]

[edit]

The MFA has gradually been expanding its programs of customs outreach to people who have non been traditional visitors, and this trend accelerated later on Matthew Teitelbaum was appointed as Director in 2015. This expansion has included improved accessibility for visitors who may be visually, audibly, or physically dumb.[34] Special programming and tours are available for bullheaded, ASL-fluent, cognitively-impaired, autistic, and medically-assisted guests.[35] In addition, the MFA has welcomed LGBTQ visitors with exhibitions like Gender Angle Fashion (2019), and in bound 2019 it installed universally welcoming signage for restrooms.[36]

Starting in July 2017, the MFA has offered a free one-year family membership to all newly naturalized US citizens under its "MFA Citizens" plan.[37] [38]

The MFA publicly apologized[39] in May 2019 after African-American and mixed-race 12- and xiii-year-quondam visitors were allegedly targeted by employees and told "No nutrient, no drink, and no watermelon", which is considered a racial slur in the US. A museum spokesperson said that the alert was really "no water bottles", but conceded that there was no mode of definitively proving what was really said. Regardless, all museum staff dealing with schoolhouse groups were to be retrained in interactions with their guests. The MFA also concluded that ii of its members had been deliberately racist, and permanently banned them from visiting its grounds.[xl] [41] [42]

On Oct 14, 2019, the MFA debuted its newly renamed "Indigenous Peoples' Day" (formerly "Columbus Day") celebrations, with a focus on Native American fine art and culture.[43] The events included special displays related to Cyrus Dallin'south 1908 Entreatment to the Corking Spirit, a popular and sometimes controversial sculpture of a Native American warrior located in front of the Huntington Avenue main entrance since 1912. Community comments and feedback concerning the awe-inspiring artwork were solicited and displayed.[43] Earlier, in March 2019, the MFA had held a special public symposium to discuss the historical background and present-solar day significance of the iconic sculpture.[44]

As of 2020[update], the MFA offers 11 annual Community Celebrations, featuring gratuitous admission for all visitors, and special events such as dance performances, music, tours, craft demonstrations, and hands-on art making. This serial includes mean solar day-long Martin Luther King Jr. Mean solar day, Lunar New year's day, Memorial 24-hour interval, Highland Street Foundation Free Fun Fri, and Indigenous Peoples' Mean solar day celebrations. In addition, on Wed evenings, which are already gratis from 4pm to 10pm, special celebrations of Nowruz, Juneteenth, Latinx Heritage Night, ASL Dark, Diwali, and Hanukkah are featured.[45]

To commemorate its 150th ceremony, the MFA offered a free i-year family membership to anyone attended one of its special Customs Celebrations or MFA Late Nite programs during 2020. This "First Year Costless Membership" program was bachelor to anyone who has non previously been a member of the museum.[46] The 150th year exhibitions included major shows and events featuring art past women and minority artists.[47] [48] [49]

In November 2020 a significant number of MFA employees voted to unionize due to a long history of unaddressed issues related to workplace conditions and compensation inequities.[50] The workers unionized with the local affiliate of the United Motorcar Workers. After over 96% of the union agreed in a vote, MFA staff went on a strike for the get-go time on November 17, 2021. Union representatives cited unresponsive appointment from MFA management over multiple issues including brackish wages, job security, and workplace variety, as the reason for the strike.[51] The spousal relationship pointed out that employee wages had been frozen for two years, and that management had so far just offered a ane.75% percent raise over the form of four years. Union representatives contrasted this with MFA director Matthew Teitelbaum'due south salary which, clocking in at nigh 1 1000000 USD, was almost 19 times larger than the average MFA worker.[52]

Highlights [edit]

Amid the many notable works in the collection, the post-obit examples are in the public domain and have photographs bachelor:

American [edit]

European [edit]

-

-

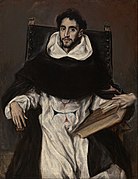

El Greco, Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, 1609

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Antiquities [edit]

-

-

Male monarch Menkaura (Mycerinus) and queen, 2490–2472 BCE

-

Winged Protective Deity, 883–859 BCE

-

Goddess Tawaret, 623–595 BCE

-

Marine Mosaic, 200–230 CE

Notable people [edit]

Directors [edit]

- Emil Otto Grundmann – beginning Managing director

- Edward Robinson – 2nd Manager

- Arthur Fairbanks – third Manager

- George Harold Edgell – 5th Director

- Perry T. Rathbone – sixth Director

- Merrill C. Rueppel – 7th Director

- Jan Fontein – 8th Manager

- Alan Shestack – ninth Director

- Morton Golden - interim Director 1993-1994

- Malcolm Rogers – tenth Director

- Matthew Teitelbaum – eleventh Director

Curators [edit]

- Sylvester Rosa Koehler – first Curator of Prints (1887–1900)

- Ernest Fenollosa – Curator of Oriental Art (1890–1896)

- Benjamin Ives Gilman – Curator (1893–1894?); Librarian (1893–1904); Secretarial assistant (1894–1925) Assistant Director (1901–1903); Temporary Director (1907)

- Albert Lythgoe – first Curator of Egyptian Art (1902–1906)[53]

- Okakura Kakuzō – Curator of Oriental Art (1904–1913)

- Fitzroy Carrington – Curator of Prints (1912–1921)

- Ananda Coomaraswamy – Curator of Oriental Art (1917–1933)

- William George Constable – Curator of Paintings (1938–1957)

- Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule 3 – Curator of Classical Art (1957–1996)

- Jonathan Leo Fairbanks – Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture (1970–1999)

- Theodore Stebbins – Curator of American Paintings (1977–1999)

- Anne Poulet – Curator of Sculpture and Decorative Arts (1979–1999)

Bulletin [edit]

A message appeared under various titles from 1903 to 1983:[54]

- 1981–1983: M Message (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

- 1978–1980: MFA Bulletin

- 1966–1977: Boston Museum Bulletin

- 1926–1965: Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts

- 1903–1925: Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin

Run across also [edit]

- List of most-visited museums in the United States

- The Lonely Palette (art history podcast hosted past MFA lecturer Tamar Avishai)

- Nagoya/Boston Museum of Fine Arts (defunct sis institution in Nagoya, Nihon)

- School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts

References [edit]

- ^ "Visitor Figures 2016" (PDF). The Art Newspaper Review. April 2017. p. 14. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts Annual Written report". Museum of Fine Arts . Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Southworth, Susan & Southworth, Michael (2008). AIA Guide to Boston (3rd ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press. pp. 345–47. ISBN978-0-7627-4337-seven.

- ^ Natasha. "John Singer Sargent Virtual Gallery". Jssgallery.org. Retrieved 2012-12-17 .

- ^ "An announcement was made..." (hathitrust.org). The Brickbuilder. Boston, MA: Rodgers & Manson. 8 (12): 237. December 1899. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Preserving History Chronicles The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Since Its Founding in 1870". artdaily.cc. Royalville Communications, Inc. Retrieved 2020-02-27 .

- ^ "Architectural History - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 2010-x-11. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Dobrzynski, Judith H. (10 November 2010). "Boston Museum Grows by Casting a Wide Net". The New York Times . Retrieved xiv May 2016.

- ^ Judith H. Dobrzynski (March fourteen, 2012), "How an Conquering Fund Burnishes Reputations". The New York Times.

- ^ "MFA Boston Will Reopen September 26 with Art of the Americas Galleries, "Women Take the Floor" and "Black Histories, Blackness Futures"". MFA. September 9, 2020.

- ^ "Lime Green Icicle Tower". Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Japanese Garden, Tenshin-en". Boston Museum of Fine Arts. 2015-03-13. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Takes, Joanna Werch (January 20, 2015). "Chris Hall: A (Japanese-Inspired) Timber Framing Philosophy for Furniture". Woodworker'due south Periodical . Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ "Avant-garde Search Objects – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to Receive Landmark Gifts of Dutch and Flemish Art Including Rembrandt Portrait and Other Golden Age Masterpieces". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 2017-x-12 .

- ^ Massive gift of Dutch art is a coup for MFA - The Boston Globe

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Announces Major Gift from Rothschild Heirs, Including Family Treasures Recovered from Austria after WWII." Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 22 February 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ "Acquisitions of the month: October 2018". Apollo Magazine. 2018-eleven-09.

- ^ "Contemporary Art". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-18 .

- ^ a b c d "Spotlight on panelist Dr. Anne Nishimura Morse, curator of Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston". Conference on Cultural and Educational Interchange (CULCON). 2012-08-17. Retrieved 2020-07-07 .

- ^ a b c d "Art of Nippon Collection and History of Cultural Exchange". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-07-08 .

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts Boston: Japanese Collections". North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources . Retrieved 2020-07-08 .

- ^ Adamson, Glenn (2020-06-13). "The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston turns 150". Apollo Mag . Retrieved 2020-07-07 .

- ^ Khvan, Olga (2015-04-03). "Two New Exhibits Tell Story of Japanese Art at MFA Boston". Boston Magazine . Retrieved 2020-07-08 .

- ^ Hintermeister, Henry (2018-02-xx). "An Fine art History". The Tufts Observer . Retrieved 2020-07-08 .

- ^ a b Billman, Ty (2020-06-12). "A Critical Moment for Japanese Art Curation". Kyoto Journal . Retrieved 2020-07-07 .

- ^ "Conservation in Action: Japanese Buddhist Sculpture in a New Low-cal". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-07-08 .

- ^ "'In Pursuit of Happiness: Favorite Works from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston". The Japan Times . Retrieved 2018-10-08 .

- ^ "Japanese Masterpieces from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston". Tokyo National Museum . Retrieved 2020-07-08 .

- ^ a b "MFA Library: William Morris Hunt Memorial Library: Home". library.mfa.org. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 2020-02-29 .

- ^ "MFA Library: William Morris Chase Memorial Library: Exhibitions". library.mfa.org. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 2020-02-29 .

- ^ "About CAMEO". CAMEO: Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "MediaWiki API help". CAMEO. cameo.mfa.org. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Accessibility". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ "Access Programs". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ "Tips for Visitors". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ "MFA Citizens". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ McCambridge, Ruth (xv May 2018). "Boston'south Museum of Fine Arts Hosts a New and Perfect Kind of Event". Nonprofit Quarterly . Retrieved 2020-03-08 .

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Announces Steps to Accost Results of Investigation into Davis Leadership Academy Group Visit on May xvi, 2019". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ Sini, Rozina (May 25, 2019). "Boston museum sorry for racist 'no watermelons' remark". BBC News . Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Garcia, Maria (May 24, 2019). "MFA Bans ii Patrons After Students of Colour Say They Were Subjected to Racist Comments". WBUR . Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ Farzan, Antonia Noori (May 24, 2019). "Black students on a field trip said they were told 'no nutrient, no drink, no watermelon.' Now the museum is apologizing". Washington Mail service . Retrieved 2020-02-xix .

- ^ a b "Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Honors Indigenous Peoples' Day with Launch Of Gratis Customs Commemoration That Places Native American Voices at the Forefront". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ "Dallin experts talk over sculptor's work, 'Appeal to the Great Spirit'". The Arlington Advocate. March 12, 2019. Retrieved 2020-02-nineteen .

- ^ "Community Celebrations". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Archived from the original on 2020-04-25. Retrieved 2021-04-29 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Starting time Year Free Membership". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts, Boston's 150th Anniversary Honors the Past and Reimagines the Time to come". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . Retrieved 2020-02-19 .

- ^ Shut, Cynthia (December 27, 2019). "MFA, Boston Turns 150: Hither'south How They're Celebrating". Art & Object . Retrieved 2020-03-08 .

- ^ Chew, Hannah T. (October one, 2019). "MFA's 150th Anniversary to Honor the By and Reimagine the Future". The Harvard Ruby-red . Retrieved 2020-03-08 .

- ^ "In a Landslide Decision, Workers at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston Become the Latest Major American Museum Staff to Unionize". 23 November 2020.

- ^ Lonas, Lexi (2021-11-12). "Workers at Boston Museum of Fine Arts vote to hold 1-day strike". The Loma.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ Levin, Annie (2021-11-17). "MFA Boston Staff Hold One-Day Strike for a Off-white Contract". Observer.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ Bierbrier, Morris Fifty (2012). Who Was Who in Egyptology, quaternary edition. Egypt Exploration Order. p. 244. ISBN978-0856982071.

- ^ "Museum of Fine Arts Message on JSTOR". JSTOR / Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved Oct 8, 2017.

External links [edit]

- Official site

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum_of_Fine_Arts,_Boston